Depicted on the canvas is a thing. The painterly language of a still-life tells us that it is an object: it is placed on some kind of rectilinear plinth, presenting a sharply defined corner to us. There is nothing in the background but colour – a depthless black or white, perhaps a queasy green or brown, an elegant purple. There, however, our certainties begin to fail us. What this thing ‘is’ is not certain. Ivan Seal paints many of them. He has referred to them in the past as ‘hand-eye parasites’: should we assume that by this he means things that assume control of his ‘hand-eye’ co-ordination to make themselves exist

Depicted on the canvas is a thing. The painterly language of a still-life tells us that it is an object: it is placed on some kind of rectilinear plinth, presenting a sharply defined corner to us. There is nothing in the background but colour – a depthless black or white, perhaps a queasy green or brown, an elegant purple. There, however, our certainties begin to fail us. What this thing ‘is’ is not certain. Ivan Seal paints many of them. He has referred to them in the past as ‘hand-eye parasites’: should we assume that by this he means things that assume control of his ‘hand-eye’ co-ordination to make themselves exist

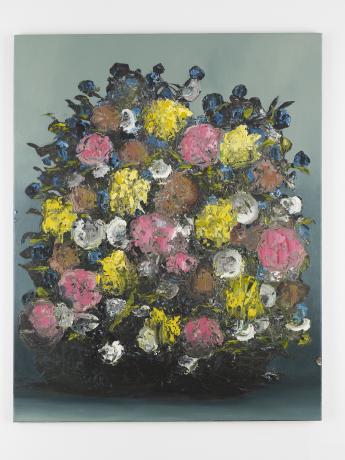

Such an object might be a bit like a distorted mass of skulls on spikes, a model of a ballerina, a fan of sectioned wood, a lump of agate, a box, a giant fabric balloon, a woodwork block with a chisel resting on it, a lump of clay sectioned with wire. It may be a vase of blooms, overdaubed, overflowing their container. It may be a branch adorned with hanging objects. It may be some kind of watch, but not a watch that has surely ever been worn, its wrist-strap is stretched, strange, somehow snakelike, perhaps reverting to the animal that gave up its skin. The strangeness of the objects, the fact that they don’t quite correlate with anything in the real world, is what they are about. They speak to us stylistically of classical painting – and their technical composition is, to this untrained eye, seriously impressive – but their content speaks of something altogether different.

I first encountered Ivan Seal’s paintings on the album covers of Leyland Kirby and The Caretaker records, three of which have just been re-released on vinyl. I chased down the tail-end of his first show at the Carl Freedman Gallery on Charlotte Road a couple of years back. I’ve just been to see the new show at the same gallery and spoke to Ivan in situ. His work has expanded, in all dimensions – the thickly impastoed oils now emerge yet further from the surfaces of the canvas, giving objects that were once sculptural again a sculptural feel.

Like his friend Jim Kirby, also from Stockport, Seal now lives in Berlin (although Seal reports that Kirby is moving to Poland) and like his friend he has worked with sound: before returning to painting five or so years ago, in fact, sound art was the form his practice typically took. There is a kinship between Seal’s painting and Kirby’s sound work that makes sense of their coupling in Leyland Kirby and Caretaker releases. The objects Seal paints are remembered from his childhood. He has not seen them for decades but they are dredged up from memory and return distorted, mutated, accreted. He does these memories great service to remake them as vivid, lurid things, but they can never be what they were. They have been changed in his head, changed by time. We realise that mental deposits are not eroded like environmental forms, or degraded like discarded metal; the cerebral equivalents of frost-shattering and rust do not destroy so much as translate. Colours are shifted, edges are blurred, shadows are cast at impossible angles and lines are drawn into thin air. References have been accrued: Bacon directly referenced in one piece. The objects have become steeped in the solution of the unconscious mind, doused in the fluid of dream.

Like his friend Jim Kirby, also from Stockport, Seal now lives in Berlin (although Seal reports that Kirby is moving to Poland) and like his friend he has worked with sound: before returning to painting five or so years ago, in fact, sound art was the form his practice typically took. There is a kinship between Seal’s painting and Kirby’s sound work that makes sense of their coupling in Leyland Kirby and Caretaker releases. The objects Seal paints are remembered from his childhood. He has not seen them for decades but they are dredged up from memory and return distorted, mutated, accreted. He does these memories great service to remake them as vivid, lurid things, but they can never be what they were. They have been changed in his head, changed by time. We realise that mental deposits are not eroded like environmental forms, or degraded like discarded metal; the cerebral equivalents of frost-shattering and rust do not destroy so much as translate. Colours are shifted, edges are blurred, shadows are cast at impossible angles and lines are drawn into thin air. References have been accrued: Bacon directly referenced in one piece. The objects have become steeped in the solution of the unconscious mind, doused in the fluid of dream.

Seal’s painting seems particularly timely to me. Philosophy is very interested in Kant right now, even if that interest is in stealing his fire, in revolving the Copernican revolution a quarter-turn again, taking the subject away from the centre of the picture. I’m not a philosopher, so I’m not going to begin to attempt to engage in that particular discourse, but what I would say is that Seal’s things seem to work in similar territory, to work at the difference between gedachtnis and erinnerung, between, very broadly, active and passive remembering. I’m going to go to Howard Caygill’s admirable A Kant Dictionary as my first port of call for all things Kant (admirable, because he guides you through the massive volume of extremely difficult work by single word themes – simply and effectively – thereby making it unnecessary to dredge through the Critique of Pure Reason first-hand – hey, this is a blog-post, right?)

Here is Caygill’s entry on Kant’s take on the memory:

Memory is defined as the ‘faculty of visualising the past intentionally’ which, along with the ‘faculty of visualising something as future’, serves to associate ‘ideas of the past and future condition of the subject with the present’ (A §34). Together, both memory and prevision are important for ‘linking together perceptions in time’ and connecting ‘in a coherent experience what is no more with what does not yet exist, by means of what is present’ (ibid.). It can thus be seen to play a significant role in the problem of identity, and more particularly, in the character of synthesis. Memory is implied in two of the three syntheses of the ‘transcendental faculty of imagination’ presented in the deduction of CPR: in the ‘synthesis of apprehension’ where it informs the consistency of appearances, and in the ‘synthesis of recognition’ where it is implied in the continuity of the consciousness of appearances. (Bloomsbury, 1995, 290-291)

Clearly, temporality is crucial to the experience of memory for Kant, and memory to the imagination, which in Kant’s thought was more literally a process of making mental images. Seal’s work seems to disrupt some of the assumptions about the temporalities of memory and to insert assorted spanners into the idea of a consistency of appearances. The things that emerge on the canvas are not recognisable in any sensible sense. In a perhaps slightly tangential way, Seal’s work perhaps has a kinship with Richard Long’s, about whom we talked briefly: there is evidently a very different approach to practice, but there is the same attention to the experience of time, the same ability to condense that sticky stuff onto a canvas.

Clearly, temporality is crucial to the experience of memory for Kant, and memory to the imagination, which in Kant’s thought was more literally a process of making mental images. Seal’s work seems to disrupt some of the assumptions about the temporalities of memory and to insert assorted spanners into the idea of a consistency of appearances. The things that emerge on the canvas are not recognisable in any sensible sense. In a perhaps slightly tangential way, Seal’s work perhaps has a kinship with Richard Long’s, about whom we talked briefly: there is evidently a very different approach to practice, but there is the same attention to the experience of time, the same ability to condense that sticky stuff onto a canvas.

Seal’s painting also seems to shift some of the agency onto the things he paints, to distance the composing subjectivity from the finished work. He gives his painting titles using a random text generator, a next generation Bourroughsian cut-up machine. This is more coherent than it might seem at first glance – there is also a disturbance of temporality in the text that we discern more clearly if we call it linearity, the way in which one word – or letter – follows another in a line of text. It also makes each thing more sui generis – the act of titling has been delegated to a machine and each thing on each canvas has become more independent of the subjectivity that put it there when it gains a name like ‘triltry konte’ or ‘pervaalfet deatpetchsplobasmag (drunk in a car no. 678 )’. A press release was also produced in the cut-up style.

It also makes each thing more sui generis – the act of titling has been delegated to a machine and each thing on each canvas has become more independent of the subjectivity that put it there when it gains a name like ‘triltry konte’ or ‘pervaalfet deatpetchsplobasmag (drunk in a car no. 678 )’. A press release was also produced in the cut-up style.

I could happily spraff on about this painting for pages because I love it but if I did I might miss the chance to recommend the show while it’s still on. It was was recently given a seal of approval (please don’t even think of that as a pun) by the Contemporary Art Society’s Paul Hobson who has this week been appointed director of Modern Art Oxford.