Earlier this summer I interviewed documentary maker Adam Curtis for Dazed and Confused magazine. Curtis generously gave me an hour of his time and was an extremely engaging and candid interviewee, running with my questions and providing answers that far outstripped their scope. Dazed were only able to run this at 1,000 words and I thought there might be interest in an unedited transcript so post this online in the hope that it might find some readers. (When I say unedited, I have of course made my questions far tighter and more coherent than they were.)

We met at Television Centre the morning before James and Rupert Murdoch were due to appear before the Commons Media and Culture Committee and sat in the horseshoe of the magnificent building, soon to be vacated when the BBC moves its base to Salford media village. Curtis mentioned that he’d been offered the use of the Centre after this move for a Punchdrunk project but we began by discussing the Murdochs and the excitement around the breaking story despite his concern that it would be out-of-date by publication. I asked if he would be tuning in to the Murdoch testimony later in the afternoon. Of course, he replied:

It’s just a great story.

How do you think it will play out?

In essence no one really knows. At the moment it’s a wonderful, wonderful story. It’s not Watergate, in the sense that it’s the corruption of power, but these scandals can often flick a switch that starts something broader.

You’ll find me resistant to comment any further. Daily journalism is about trying to record, as best you can, the fragments you have in front of you. What I tend to do is come along later and try and pull all those fragments together and say what does it all mean or have you thought of looking at it this way. When you’re living through something you absolutely no idea what it means. That’s part of the thrill of it. You can speculate. I really don’t know.

What do you think of the current state of journalism?

This whole argument that the internet is destroying newspapers is a bit of a smokescreen. I know it’s taking advertising away from newspapers, but it’s also that the journalism is so boring.

If someone like, say, the New Journalism movement of the early 1960s came along and reinvented journalism – which is story-telling about the real world – in a way that connected with the way people think and feel today, then people would buy that newspaper or magazine or whatever it was because they’d want to have it. At the moment the journalism we have most of it is written in such a way that it feels very out of date, it doesn’t connect with the way we feel about the world, it’s not real to us. Murdoch journalism has never felt real, it’s always been a comic product. Broader journalism now feels very unconnected, not with the things it’s describing, but with the sensibility of audience, which has changed radically in the past five or ten years. The sensibility of an audience now is much more fragmented, much more shifting, much more emotional. If you live in an age where there are no big stories anymore, what is substituted for that is an emotional response. That’s not wrong, that’s just what happens.

The realism of our time – to use a literary term – is a fragmented emotional one. That’s how most people experience the world, as fragments which they fit together emotionally. The internet encourages that, you flit around that, you experience that in a fragmented way. I notice that story-tellers – and myself when I edit – I find I’m much happier, and my audience are much more happy, with big emotional jumps. They like it and they like filling in the gaps themselves.

Traditional journalism still tries to be much more causal and analytical. That’s fine except that the audience knows that most of those journalists have no idea what’s going on, we have no idea what’s going to happen in Europe, we have no idea how this scandal’s going to play out – so when we try to do this causal analytical approach it feels thin and somehow false and the audience knows that.

Each age has its own way of experiencing stuff and our way is very emotional and associative. Now, someone is going to come along and create a kind of journalism that both reflects that and connects with that yet at the same time takes people out of themselves and describes the world in a broader way than they can experience through their own narrow experience, that somehow feels real to them.

New Journalism. I think we’re on the cusp of that. I don’t think it’ll come through television, I think it’ll come through writing, and when it does, people will love it, because they want to be taken out of themselves and then they will buy the product that has it in it and they’ll pay a lot of money for it. So I don’t think that print journalism in the general sense is over. That’s a smokescreen. It‘s because it’s boring and it doesn’t connect.

If you live in an age of individualism – which is what we’re encouraged to be, and what we want to be as well, it’s us… at the moment – you judge what is right and what is wrong by what feels right to you. What did Tony Blair say about Iraq and the ultimate justification – I’m misquoting but it’s pretty much what he said – “I did it because it felt right to me.” And that, in our age, is the guiding principle by which you judge. It’s not that you are told that it’s the right thing to do, that’s how it used to be, it’s whether it feels right to you now.

That’s what I was trying to trace in The Century of the Self, the rise of that idea and those who would then take that new idea that feeling was important and shape it and use it for their own purposes. It had to exist before they used it. And I don’t think journalism’s really caught up with that. In a funny way politics did under Blair, and now it’s lost it again partly because the world’s got so confused and the strange territory that Blair took it into as a result of that.

If you live in an emotional age then of course it’s going to be a confused age because there isn’t an elite telling you a story by which you can judge events. So what in effect happens in that age is that events come and go like the waves of a fever and sometimes they come into focus and like in a fever they’ll float out of focus. That’s the realism of our time. In many ways it is more real than previous ages which tried to tell you a grand story. Now, the question which no one really knows the answer to is whether that’s what we’re in for the long run. I mean, the patrician age of mass democracy lasted from the middle of the 19th century really to the early 1990s. We may be into another period of that. Or it may be the blip between the collapse of one big story and the rise of another. And you could say that the whole problem with the press – including the Murdoch thing – is that they don’t have a big plot – in literal terms they’ve lost the plot – there isn’t a plot. If you’re in a newsroom in The Mirror, The Sun, or The Telegraph, The Guardian, when an event just happens there isn’t a big plot, there isn’t a frame into which to fit it. So things come and go. Journalists have lost the plot. People turn away from that kind of journalism because it doesn’t connect with them.

No one knows whether that’s going to last. I suspect that it probably won’t. Some big, serious cataclysm is going to happen, it may be a big, really serious economic crisis that hasn’t happened and out of that will come the necessity for a big story.

What role does a historically engaged journalism such as you produce play in that?

I do two things: I trace how that happens but also, I think that I feed off that mood. I’m very emotional. The way I do my journalism also tries to rework journalism so that it’s couched in those terms. The way I edit is much more associational and fragmentary than previous ways of telling stories on television. And also, I’m quite emotional. I take quite serious subjects and quite causal and analytical arguments – my films are quite old-fashioned – and I try – sometimes successfully and sometimes not successfully – to integrate that and fuse that with emotion so you feel that as well. I use music, images and my voice to create a mood because I think mood is incredibly important to get something over to people. It doesn’t mean that you are then incoherent or emotional yourself. What I’m saying is very straightforward, causal and analytical but you create a mood platform on which you tell that story. And people like that. They just do. Because mood is the thing of our time. That’s why people like immersive theatrical experiences like Punchdrunk. What Punchdrunk do brilliantly is create a mood. They’re just brilliant at it. The extent to which you can then create a story, I don’t know, we ran into problems with that one.

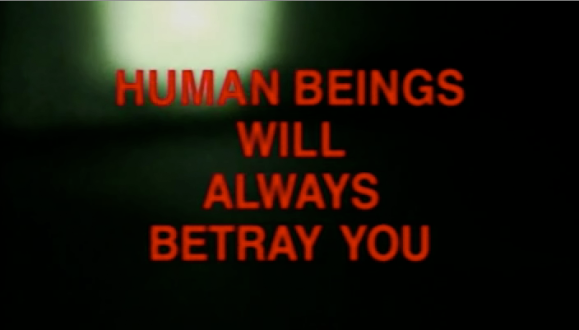

Your captions have begun to seem more and more like artistic interventions: they remind me of Jenny Holzer’s work.

People have said that but I don’t know her. I don’t really know about art. That really comes out of wanting to use songs. I didn’t want my voice to get in the way of the songs so I used captions. People are really happy with films that have a varying texture.

I’m quite normal. Given a bit of confidence by this lot but basically I’m quite normal. So if I like it, if I think it’s a bit silly or a bit funny or a bit appropriate then I think people will probably think that as well.

Can you imagine working outside the BBC?

No, I can’t, because I sit on top of the world’s biggest, richest, most wonderful archive, a record of the past, what? 80 years? They have been so wonderful to me because they allow me to explore that archive. And I’d have to go and do something else.

How do you negotiate working with the archive and are there any particular issues surrounding that? What is already left out of the archive?

We have a record that is seriously just fragments, and out of those fragments we stitch together stories about the past. And what I do is go back and re-stitch those fragments together in other ways and say well have thought about looking not just at then but also at now in a new way. Everything is fragments. That’s what reality is. And all journalism and politics is is taking the fragments of experience, dropping most of them and stitching together the ones you want to tell a story that makes sense of the chaos of the time. As I said, when you’re living through something it makes no sense. It’s afterwards that you look back on it and make it into a story yourself, whether it be a love affair or as day you lived through or whether it be a grand event, we all individually and collectively, stitch together, and politics and power is fundamentally a debate about how you stitch those fragments together and the change in the structure of power is when, in a way, those fragments are re-stitched, reworked. That’s what happened in the 1970s when you got the collapse of the idea that politics and the state could control everything. And it was reworked into a sort of technocratic, strange version of the free market, where in a way, the state takes a lesser role and individual’s choices and things can be catered to by other organisations.

No story just happens, it’s made, and here is one of the great factories which constructs that frame. And all the people you see around you are the construction workers of the story we live through. Whether they’re on Newsnight or on a reality show, they’re construction workers, we’re all construction workers.

I’m a parasite construction worker in the sense that I come along, take the fragments that have already been stitched together, pull them apart, rework them and ask have you thought about things in this way, and I do that because I think we live in this inter-regnum between frames.

I try to give people confidence that what you’re told is not absolute truth, it’s a construction. And let’s understand, it’s not a conspiracy or anything like that, it’s a construction. Let’s see a) how a construction is made and b) that you can construct it this way or that way and what do you think? If a big news story comes along people like me will just disappear out the frame.

If I was to make a serious film next I think I would like to go back and examine was that really the free market? Was it a sort of scientific, technocratic version of the free market that we’re still stuck with.

When you talk of big stories it makes me think of Lyotard and grand narratives, and your critique of structures of power is reminiscent of Foucault. Is your work informed by theorists such as these?

I have really serious problems with academia. I would never ever use those terms because a) they intimidate people and b) people don’t understand what you’re talking about. And actually what they say can be put very clearly in simple language, that’s what journalism is all about. Of course I am aware of those things and what they say is not really very profound. The world is constructed, how we see it is constructed and who constructs it has a great deal of power and every now and then that frame cracks and is replaced by another one. That’s called the struggle for power.

People then go and write books full of very long words that are saying that same thing but basically mystifying it, and preventing people like myself, who are normal but quite clever, from understanding it because it’s intimidating.

The only thing I’m interested in doing is communicating ideas to other people and saying ideas are quite powerful and important. Why dress it up?

Actually, I think academia is one of the institutions that should be examined. I think it has a really destructive role in stopping people thinking. Far from liberating people they actually intimidate people from thinking freely and more widely and more imaginatively, which actually should be their role. I’m in a privileged position, I’m allowed to make films which try to explain the world to people. I have never ever used a word that I thought people would not understand.

People would also, if they had any confidence, laugh at that language, and quite rightly so.

People talk about Foucault. What he says can be put in very simple, clear terms. I’m not trying to dismiss what he said, I’m trying to dismiss the terms in which he has written and the terms in which he is written and talked about. It’s anti- everything I believe in, which is clarity, and trying to give people the confidence that I was given by a good education which came about because of the state and also by good university teaching.

That confidence led me to believe that you can take any idea and explain it clearly and imaginatively to anyone. And the academy seems to be actively in many respects working against that which makes me think that it might be in decline.

In the late 1980s what went on in the Humanities in academia in Britain and America was as absurd as what was going on in the Soviet Union’s academies when they were trying to prove that the Soviet plan really was working by things that didn’t exist.

I also have problems with academia, because as a journalist I go and read a lot of academic books and to give them their credit they have good facts in them and they tell you interesting things but what I find with academics is that they won’t speculate. And it’s not because they’re stupid, it’s because they’re frightened, frightened that their colleagues will jump on them. It’s most dispiriting and unhelpful. Your heart sinks.

I’m still waiting for a new generation to come up in history that really want to tell stories, that don’t just want to theorise too much, that’s not to say you can’t have a theory. In many of my films I have theoretical arguments, but I would never put it like that.

But surely there are bigger problems with more popular ways of doing history?

The problem with popular history is that it over-generalises. It tells you what you already know and if it does that you switch off, you think I already know that, and you stop listening. Novelists have devices. What we need to do is to find similar devices to take you into that world. In the Century of the Self I used Sigmund Freud’s nephew, who I discovered in an academic book, and who claimed he’d used his uncles theories.

You begin to look at the world of PR and advertising in a new way. Throughout the series I kept on coming back to the Freud dynasty.

The problem with popular history is that it doesn’t tell stories, it just gives you the received wisdom, and people just go I know that and they don’t listen.

Can I pick up on what you mentioned as we were coming in, and ask you about Punchdrunk and doing a project here at the BBC?

The thing to do here would be a ghost story about all those fragments that are sitting in our library. There would be millions and millions of fragments of experience recorded. And maybe over the last 80 years something’s been moving through it. I would do a ghost story based on that idea. It would start on television sometime before. And ultimately it would end up with people on the day this building closed, the doors would be open and anyone could come in and go anywhere they want but what they would discover is that something that had already be on television would be continuing in here and it would be like in a ghost story.

It would be the ultimate opening up of the public service broadcaster only to find something strange at the heart of it. Everyone would be gone, this building would be completely empty, but you would begin to discover things, which you’d have to piece together yourself.

The problem I discovered when I did a thing with Punchdrunk was that as opposed to television, when even if you’re being emotional and you’ve gone away from your story for a bit ultimately you come back to your story, in a Punchdrunk thing you can go wherever you want, you’re making your own story, it’s actually very difficult to then tell a big story. It doesn’t cohere. The thing I did in Manchester with them was actually about how the fragments don’t cohere so it seemed an appropriate use of those limitations. What I couldn’t do was tell the audience something new. If one could somehow find a way of engaging people through the immersion that Punchdrunk do and at the same time fusing that to a narrative that told them…

I know Felix who runs Punchdrunk said he had real problems with the Duchess of Malfi – the play out in Docklands – he had real problems with that.

No one knows how to do that. The internet can’t do it, film can’t do it, immersive theatre had a stab at it. It may come through literature, I don’t know. I suspect someone will write some kind of novel that will send you somewhere. Somehow someone will fuse a film, a book sending you somewhere.

Back in the 1920s people really loved puzzles. Great thick books of puzzles, where you had stories where you had to work out diagrams. They reminded me of computer games.

While we’re on the subject of collaboration, I was wanting to ask about something that I’d read in Private Eye, that you turned down a commission from The Guardian?

No comment. Is that what Private Eye said? I didn’t see it. I did.

Another collaboration I was wanting to ask about was your film for Charlie Brooker’s Newswipe?

What I think Charlie Brooker has got is he’s one of the few journalists who gets the modern age. What he reports on is how he reacts to things. That is the journalism of our age. Because what people are concerned about is how they feel. I go back to what we said right at the beginning: ‘it feels right to me’ is the thing of our time. What Charlie does is he literally reports to you how he feels, how he reacts to something, whether it’s a television programme, or, I dunno, the Murdoch thing. He’s describing the events but he’s also describing how he feels about them so it has an authenticity to it, and it’s a modern authenticity. It’s narrow and it’s narcissistic, because it’s all about how he feels, but that is the realism of our time, you can’t escape it, and he’s got it and that’s why I think he’s really good and that’s why I feel privileged to be allowed to make films for his programme. He is one of the early construction workers in what I think is going to be the journalism of the future. Something that somehow when people read it is going to make them think: ‘That’s it, that’s how I feel.’ Because at the moment so many of our news programmes just literally tell you about your own experience because they’ve discovered that’s how you get an audience. So for example Panorama will – and this is not criticism – Panorama increasingly finds itself making films about, I dunno, car insurance fraud. It’s not a bad story, but it is just about what you already know. That’s fine, and we should be making those films, but we have to move outside of that.

Do you think there’s a risk that this affective mode of doing journalism doesn’t move us beyond being trapped in our own feelings?

Well, yeah, it’s limiting. We live in a very limited age, it is an age where we are trapped by our own sensations and everything around us is about validating that and saying that is the right way to be. In many ways it’s wonderful because we’ve been liberated from the old hierarchies of the past and the old elites of the past who told us how we should feel. Our archive is full of people from the 1950s onwards telling you how you should feel and how you should think. And just trusting your own feeling is quite empowering but at the same time it’s quite limiting and its limiting in two ways. Because it means all you know is what you see and what you feel and also if you are on your own and things go wrong it’s quite frightening. And when things do get bad for people – and they may get worse – when you live in world where you are just encouraged to trust your own sensations and things go bad, there’s nothing else around to help you. And I think that is why there’s such a sense of anxiety around at the moment. Journalism tends to feed off that. You get waves of apocalypse journalism, or avalanche journalism, waves of fear sweeping through. The reaction to al q’aeda was one of those that I tried to argue against, that a serious terrorist threat was being magnified out of all proportion and sweeping through society. It can only do that because it has a purchase on a fear or a feeling in the back of people’s minds and I think a lot of that is there because in an age of individualism when things go wrong it is quite frightening. If there is a big economic crisis there will be more fear and a bigger sense of isolation and loneliness. It’s also disempowering because what it stops you realising is that actually together you are stronger, and you can challenge power and you can change the world. And I think that’s the thing we’ve forgotten. It may come back or we may be in this for the long run. I don’t know. But journalism hasn’t even really caught up with individualism, it hasn’t actually created, to use an academic word, a discourse that describes the world to people in ways that connects with their individualism. So quite naturally they turn away from journalism and turn to each other, actually, and just chat, and live their own lives. It’s what I call the Richard Curtis ideology, that all you have in the world you and your own sensations and your own circle of friends – because that’s all his films are about. I think that’s very narrow and quite dangerous. That may lead to problems in the future. What people like me are trying to do is to connect with that emotional way of seeing the world.

That’s what the world is about at the moment, it engaging with that, it’s not narcissism, it’s individualism.

I’d like also to ask you about music. The music you use in your films is striking and very catholic, drawn from all sorts of sources. How do you encounter music? Is the music in your films representative of what you’re into?

A lot of my friends have got into the habit of pointing me in the way of music they like and giving me stuff. My mood changes. For example, Nine Inch Nails. Completely by chance I was staying with a friend in America and I had jetlag and so one night I was playing his Itunes thing and I literally by mistake played a Nine Inch Nails song and it was very romantic but it used industrial noise and I thought this is wonderful and I started listening to a lot of them and the last series is slathered in them. People quite like the idea of something that is almost falling apart but is somehow held together.

I listen to stupid pop which is my great love. Never go with the fashion of the time. The problem with a lot of music at the moment is that it’s completely in the hand of PRs. I get quite a lot of people come to me and say “will you do a video for us?” and so I listen to their stuff and so many bands are an archaeology of the 80s, that kind of post-punk stuff, early to-mid-1980s. You just have to listen. Often the most stupid things might work against a piece of footage. There was a bit in the last one where I had a shot of Monica Lewinsky and Bill Clinton and I slowed it down and cut it to a song by Leonard Cohen, who normally I would never like, but it just worked.

If it feels authentic, people somehow get that mood. You know those documentaries that have that dreary ambient drum and bass with a little bit of skittering, and there’s almost like a central factory that feeds this into documentaries but because you notice that they haven’t done it in any way to enhance the image, they’ve just needed to fill something in their structure, in a way you go off the film. You don’t feel it’s an authentic response.

The other way I use music is its punctuation, it’s a full-stop or a comma, it’s just grammar, it’s all it is. I listen to just masses. I have a drive with about 72,000 tracks on it. At the moment I’m listening to early recordings of opera – 1900s, Caruso and stuff like that, very, very scratchy stuff.

The film I’m cutting at the moment about the press in the 1960s, I’m using a lot of hard guitar music from the 1990s like Jesus and Mary Chain and more obscure bands, because it just feels right. It has to be very pop, have loud guitar, and that one drum noise, which is flat.

Using opera was a 1980s thing in films, all that minimalist stuff, Philip Glass. The ones I really hate – and this is bitchy – the documentaries I have a real problem with are the ones that use Arvo Part on their films. I’m sorry, this is not a criticism of Mr Part, but somehow the combination of the music of Arvo Part and, I dunno, dead bodies in Bosnia, just… again, it stops you looking at it and experiencing it for what it is, it’s like a cliché, you hear the language of the film-maker, it’s what you’d call modern plangent and because it’s so concerned with trying to convey something it actually conveys nothing, whereas to convey things you have to surprise your audience.

I did it to a very silly song from the 1960s cut very fast, just to make you look at it afresh. It’s silly but it’s sarcastically silly, it’s playing against it. Basically, one has to play against the knowledge that your audience already has about what the film is trying to tell them. Basically, audiences are really mature these days and they know all the different types of films and the way they tell you things. I’m not being deliberately contrary, I want to intervene in that a different way.

I’m sure you’re tired of this particular question, but I’ve read that you’re a first reader for Popbitch?

I’m good friends with Camilla who runs Popbitch. Every now and then I’ll send her a silly animal story. Popbitch has bought a racehorse, Super Injunction. I went to see Super Injunction race last night. She came last. She’s young, it’s her third race.

During the interview Curtis’s sister phoned to let him know that there was a photo of their dad in the G2 section of The Guardian illustrating a listing for the documentary Britain Through a Lens. Curtis’s father Martin was a cameraman who worked with Humphrey Jennings and was part of the British Documentary Movement.

I asked: so it’s a family business, then?

“He was a sensitive and modest film-maker. I’ve never been accused of that.”